Unlocking The Secrets Of The Guitar Fretboard… Or Any Fretted Instrument (Part 1)

How many of you struggle with figuring out the notes you are actually playing? You found an arrangement of that song you were longing to play but… it is on standard notation, you kind of know how it works but you don’t have a clue how to translate what you see on the paper to the guitar. Maybe you are that kind of player tired of reading tablature and wants to bring your knowledge of the instrument to the next level. You watch all these people on videos saying “yeah, this is the G major 7th arpeggio” and you are sitting there watching them seamlessly playing that arpeggio up and down the fretboard while you are asking yourself “how?”. If you fall in any or all of these categories you might want to read this article.

At the early stages of learning, many of us learned scales and chords by looking at tablature, at diagrams or, with the advent of video streaming sites, by watching somebody telling you what to do. That is not obviously a bad thing, on the contrary, it is a very simple yet effective way to start learning to play the guitar and understanding how it works, but when you start diving into more complex chords, modes or simply trying to figure out music theory concepts on the guitar, keeping that approach (using tablature, diagrams, videos, etc.) might not work the way it used to.

I have come to realize that one of the most important (and undervalued) skill for us guitarists, aside from having a decently trained ear, is knowing the notes on the fretboard. Why do I consider that to be the most important? Because learning the notes on the fretboard not only allows you to know the notes, it unlocks the ability to create customized scale shapes that fit your fingers (or to challenge them), allows you to come up with great sounding chords shapes and, if you are starting to improvise, allows you to play fluently… You will free yourself up from constantly thinking in shapes, you will focus more on the lines you play, you will be able to create your own riffs and licks knowing what you are doing, and you will focus more on the music. When you master the ability of knowing the notes on the fretboard you will feel like a machine that only sees note names (and/or colors or tones for the prodigies) instead of just abstract and boring rectangles on a long piece of wood.

The Basics

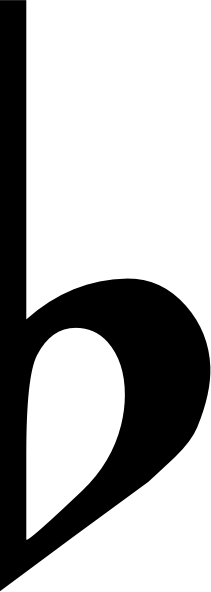

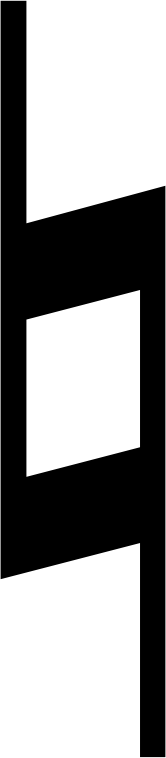

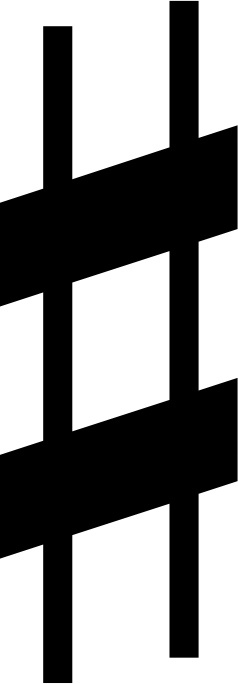

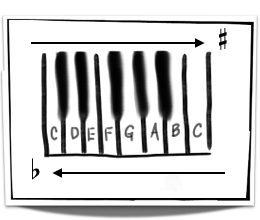

Before we jump right onto the guitar, we need to first understand how naming the notes works. It is easy, just be patient. In music the most common intervals used to describe how close or far apart 2 different notes or pitches are, are the 1/2 step (minor second in theory books) and the whole step (major second). A whole step or major second is the sum of two 1/2 steps. We have 3 accidentals that are used to describe a 1/2 step down, a natural and a 1/2 step up:

Flat

Natural

Sharp

The FLAT lowers down a natural note by a 1/2 step, the NATURAL is just a natural note (the white keys on the piano) and the SHARP raises the pitch of a natural note by a 1/2 step. Now that I mentioned the piano, let’s use its layout to better explain myself. The layout of the piano keys is for me the most clearest way to understand how you figure out note names. I call it the note calculator.

Almost everyone knows the name of these notes:

C D E F G A B C

On the piano they look like this:

The scale above is the famous C major scale. The two C’s you see on the drawing above are the same notes, they are just what in music is called an octave apart. The far right C is an octave higher than the far left C.

Finding the accidentals

We now know that the layout of piano keys is a pattern of 12 keys repeated throughout the instrument. We have 7 white keys with different names (C, D, E, F, G, A, B) and we have 5 black keys. Now you may ask, what are those black keys for? Those black keys are the ones where the FLATs and the SHARPs are located meaning, both accidentals (flat and sharp) are located on the same key (more about this later), it all depends the direction you are going. If you are going from low to high (left to right) SHARPs are the accidentals we will use to name the black keys. If we go the opposite way (high to low) we will use FLATs. That is an important concept related to how notes are named.

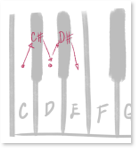

It is important to note that on the piano the 1/2 step is the interval you get when you play key after key without skipping any. To name the black keys, let’s go from low to high first. We will start from the C on the far left and then we will go to the next immediate key which is our first black key (our first 1/2 step up). To name that black key we have to use the same name of the key we started on, in this case, C, and since we are going from left to right and we already know the accidental we use when we go in this direction is the SHARP, we will just need to add it to the note name, getting a C# (you read C SHARP). This means that from C to C# there is a 1/2 step or a minor second. Remember, every 1/2 step up or down is called a minor second.

Now we jump a 1/2 step up from that C# onto our next immediate key which is D. Next, we jump a minor second up from D to the following black key. Following the previous pattern, that black key will have the name of D#. From D# we jump another 1/2 step up (minor second) from D# to the next key E. Our calculator will now start looking something like this:

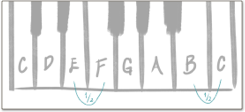

Now you ask, “what about E and F?… there is no black key…” Good question. If you look carefully, there are 2 places on the keyboard where you don’t have a black key in the middle, between E-F and B-C. Because there isn’t a black key that means that between E and F there is a 1/2 step (minor second). The same applies between B and C.

But, Couldn’t I name the key F as E# or B# instead of C if I follow the pattern? That is also a great question and the answer is, you can, it all depends in the context that E# or B# is. Heck, there are also DOUBLE FLATS and DOUBLE SHARPS! Let’s keep this simple for now, we will dive into all of that later

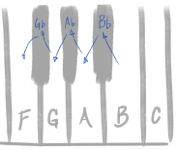

So for now, the key E stays E and the key F stays as F. If we keep following the procedure we have been using, the remaining 3 black keys, will be an F# between F and G, a G# between G and A and an A# between A and B:

Great, now lets find the FLATS

Finding the FLATS works the same way we used to find the SHARPS. The only difference is that we are going to start from the C at the far right and we will go down using 1/2 steps (minor seconds).

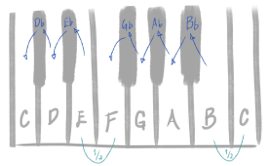

We already know that between B and C (or C and B this time) there is a minor second. We are on B now, and if we go down another minor second, we arrive onto the first black key going from right to left (or high to low). We will use the same name that preceded that black key (this time B) and we will add the FLAT to it, getting Bb (read B Flat). From that key we go down another minor second arriving at A. Next, another minor second down to our second black key this time with the name of A, we add the FLAT to it and we get, Ab. Another minor second down, and we arrive at G. Then we go 1/2 step down, to the third black key, use the name that preceded that key (G), add the FLAT, and you get Gb. Another minor second down and you will get to F.

F and E stays the same. If you keep going by 1/2 steps from E you will get all the FLATS:

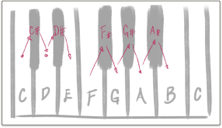

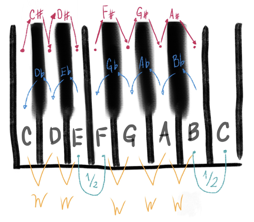

If you were to draw our note calculator with every single element that we have talked about so far, the drawing would look like this:

You will notice that the black keys can have 2 different names, they could either be a SHARP or a FLAT. Deciding which name to use depends on the scale or chord they will be used in. A scale (either major or minor) or a chord, are concepts we will be learning later to better understand music theory.

This bring me to mention that having two different “pitches” or notes on the same key or fret is called ENHARMONIC SPELLING. In EQUAL TEMPERAMENT (see appendix) both C# and Db are the same pitch, black key or fret, there are almost no distinguishable acoustical differences between them, they are ENHARMONIC. The same applies to the other chromatic notes: D#/Eb, F#/Gb etc, just like the drawing above.

Congrats, you just figured out all the FLATS and SHARPS used in music to figure out scales, arpeggios, chords, minor and major keys etc. What is best, you just figured out what in music is called a CHROMATIC SCALE. A chromatic scale is a group of notes played sequentially by using only 1/2 steps (minor seconds). If you play from C to C using minor seconds you will get a chromatic scale. You could call it a C chromatic scale but in music we don’t tend to give an specific name to CHROMATIC SCALES. Chromatic notes are a very important part of music because using they can add more color to a melody or a chord. Think of the CHROMATIC SCALE as having an art palette with acrylic paint of different colors on it, ready to be used. It may not produce something desirable in you when you look at it but you know that if you or somebody use those paints to paint a landscape, you would end up with something far more interesting to look at because the colors were combined and carefully chosen to create other color tones or to create and embellish the sky or the grass.

Appendix

For those interested on the scientific side of music, the phenomenon of having two different note names on the “same pitch” came from an attempt to divide an octave into 12 equally separated pitches many years ago, the reason why the piano has 12 keys each with a different name. This was called EQUAL TEMPERAMENT a type of tuning that basically minimized the real acoustical differences between a natural note, a Flat and a Sharp. There are a few other types of tunings each with different characteristics and uses. You see, in reality and according to science, Flats and Sharps are not the same note, a Flat is slightly lower in pitch than a Sharp. This is something a person with perfect pitch can distinguish. We will probably be able to do so as well but we would need to be born again and be trained by musicians from the cradle in order to actually learn how a flat and a sharp sounds. No wonder why Middle Eastern or Indian music sounds so different and unique to our ears, they can hear many of those minimal differences and use them too.

If people were to build instruments that would actually produce each note at true pitch, these instruments would end up being almost unplayable and totally unpractical, like trying to build a guitar with a different fret for a flat, a sharp and a natural note. That is one of the reasons people decided to use EQUAL TEMPERAMENT once it was understood and developed, to shorten the acoustic differences between pitches and able to build more practical instruments like the piano, the organ, the guitar etc. More about this at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Equal_temperament

Getting familiar with how naming the notes works is a very important step in learning the note names on the guitar or any other fretboard instrument. In part 2 of this article, I will be applying everything you read here, to find all the notes on the fretboard, so please, be sure to review very well what this first part offered to you before moving on. One thing you should be aware of is that what you learned here applies to all instruments. Knowing how to name FLATS and SHARPS using 1/2 steps (minor seconds), is the very core concept of how music works. There is much to it but it is very important to understand it if you want to know more complex concepts.

Thank you so much for reading, see you next time!